But the Trump administration is playing fast and loose with a dangerous weapon

“DONALD TRUMP is the sort of guy who punches you in the face and if you punch him back, he says ‘Let’s be friends’. China punched back and he retreated. The Europeans told him how beautiful he was, but they got nothing.” This is how an American official-turned-executive describes the latest twists in the Trump administration’s sanctions policy, which this year has roiled business from America to Europe, Russia, China and Iran. What business leaders see, analysts say, is a punitive approach that is capricious, aggressive and at times ill-prepared. But unless companies or their governments take the fight all the way to the White House, they have little choice but to abide by the long—and sometimes wrong—arm of American law.

The capriciousness was evident on May 13th when President Trump executed a handbrake turn on ZTE, the world’s fourth-biggest telecoms-equipment maker, which is strongly supported by the Chinese government. It had been brought to the brink of bankruptcy after the American government in April banned its firms from supplying it with components. That was punishment for ZTE’s violation of American sanctions against Iran and North Korea and for its subsequent lies about how it censured the staff involved.

In two surprise tweets, Mr Trump said he was working with China’s president, Xi Jinping, to bring ZTE “back into business, fast” and that the lifeline was part of a larger trade deal with China. American congressmen said this smacked of submission to retaliatory pressure from China.

Not only was Mr Trump’s move an unusual intervention in a law-enforcement matter. It also came on the day that his national security adviser, John Bolton, threatened to punish European firms that violate new sanctions the Trump administration is imposing on Iran after withdrawing from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), a nuclear deal implemented in 2016. In other words, a convicted Iran sanctions-buster allied to China might be let off, whereas firms allowed by European law to trade with Iran will be under the cosh—unless their leaders fight back.

Whether or not there is the stomach for such a battle is the question haunting businesses in Europe. French carmakers, Total, an oil supermajor, and Airbus, an aircraft manufacturer, developed stronger business ties with Iran after European sanctions were lifted in 2016. Peugeot and Renault sold more than 600,000 cars there last year. Total has signed a $5bn deal to extract natural gas in Iran, in partnership with PetroChina, a Chinese counterpart. Iran has ordered 100 planes from Airbus. SWIFT, an international bank messaging system based in Belgium that is used for business payments, reconnected Iranian banks to the global system in 2016.

Can the bloc block?

European leaders attempted this week to work out a plan for keeping the JCPOA alive without America that would enable their businesses to continue to trade with Iran. Ali Vaez, of the International Crisis Group, a consultancy, said that to keep Iran on board with an amended agreement, the Europeans may need to promise that it could keep selling its oil to them, as well as keep access to SWIFT. But in order to do that, Europe faces “a set of ugly choices”. These include threatening to impose tariffs on American imports if the Trump administration slaps secondary sanctions on European firms trading with Iran, or imposing “blocking legislation” of the kind introduced in 1996 to protect its companies from Cuba-related sanctions. “The exemption for ZTE is a good example that if the EU were to bring out the big guns...then it can negotiate exemptions,” Mr Vaez says.

But many doubt Europe’s appetite for a fight. “In my wildest dreams, I can’t imagine Europe doing it,” says Amos Hochstein, who, as a member of the Obama administration, led the move to put sanctions on Iranian oil in 2012. Patrick Murphy of Clyde and Co, a law firm, says the proposed Iranian sanctions are too different from the Cuban ones for a similar remedy.

Moreover, says Mr Murphy, in an increasingly dollarised world, businesses and banks are so worried about being shut out of the financial system that there is in fact “over-compliance” with the legal requirements imposed by America. He says this explains the sluggish pace of European investment in Iran in 2016-18, even though European sanctions had been lifted. On May 16th Total said it would unwind its investment in Iran by November unless American authorities granted it a waiver. It said it could not afford to be exposed to sanctions, which might include the loss of financing in dollars by American banks.

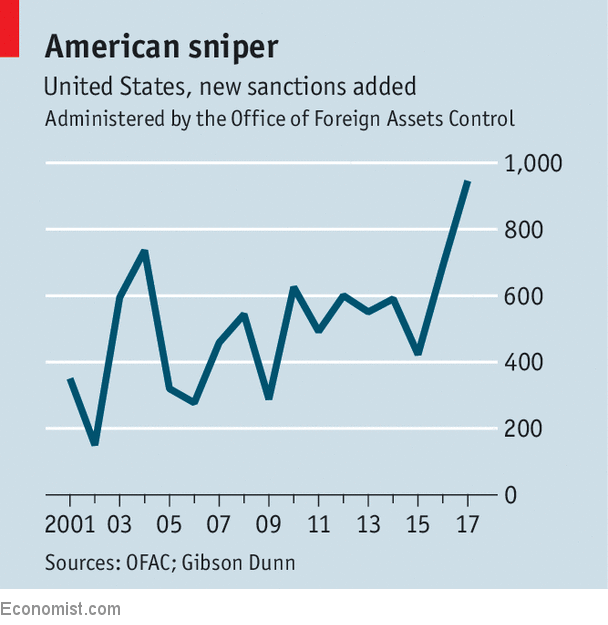

Firms face many other complications. According to Gibson Dunn, a law firm, America’s reliance on sanctions to tackle terrorism, nuclear proliferation, human-rights abuses and corruption has ballooned since Mr Trump took office. Last year it put about 1,000 entities on its “blacklist”, almost 30% more than in Barack Obama’s final year (see chart). The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), which enforces sanctions from Washington, has attracted unprecedented attention from Steven Mnuchin at the Treasury. “To the best of our knowledge, there has never been a treasury secretary so clearly enamoured with the sanctions tool,” says Gibson Dunn.

As a result, OFAC is “incredibly stretched”, says Elizabeth Rosenberg of the Centre for a New American Security, a think-tank. That makes it harder for businesses to seek clarity on the reach of sanctions. OFAC has recently lost its director, John Smith, and another senior official. This staffing shortfall may contribute to a further difficulty for business: the Trump administration has, at times, imposed sanctions without appreciating the consequences of its actions. Its crackdown on Rusal, Russia’s biggest aluminium producer, in April was aimed at punishing Oleg Deripaska, a Russian oligarch, who owns it through EN+, a company recently floated in London. But it caused immediate disruption of the world’s aluminium market, of which Rusal supplies about 6%.

Higher aluminium prices hurt carmakers, manufacturers of cans and other users of the metal, leading to a strong lobbying effort in Washington. Less than three weeks later, the Treasury watered down the sanctions by extending the “wind-down” period for firms to finish doing business with Rusal. It also gave EN+ a chance to save itself and Rusal from the sanctions if it sold off Mr Deripaska’s stake to below 50%—provided it can find an investment bank brave enough to help it with the transaction.

Ms Rosenberg says it is the Treasury’s job to anticipate what the market and political reaction will be, rather than imposing sanctions and then “walking back in the face of protests”. Others say that the more sanctions are seen as “transactional”, the more their credibility is damaged.

Yet however murky America’s system has become, businesses are in no mood to dismiss it. Doing business in countries that have been labelled as rogue regimes is not much good for their reputations. And much as they may dislike being a tool of Mr Trump’s unorthodox foreign policy, they know that they cannot disregard it.

Economist

0 Comments